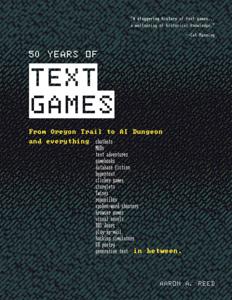

50 Years of Text Games: From Oregon Trail to AI Dungeon

Tags: #technology #gaming #history #culture #design #innovation #ai #interactive fiction #virtual worlds #online communities

Authors: Aaron A. Reed

Overview

50 Years of Text Games tells the story of the first half century of the text adventure and interactive fiction. I’ve chosen one game from each year, 1971 through 2020, to create a narrative journey through the genre’s evolution: from early experiments like The Oregon Trail to modern classics like Photopia. For each game, I explore how it works, who made it, and its enduring impact on later games and the wider world of technology, culture, and storytelling. Games featured in the book range from million-dollar commercial hits to forgotten experiments, from single-player puzzle fests to sprawling multi-user worlds. They’ve been coded in languages from Fortran to Javascript, and designed by everyone from hobbyist teens to professional novelists. But they all share a common thread: using the power of language and interaction to create experiences that wouldn’t be possible in any other medium. The book is written for both fans of text games and curious newcomers, as well as for game designers, writers, and anyone interested in the intersection of technology and storytelling.

Book Outline

1. Introduction

This section provides an overview of the text-based computer games and their evolution from rough-hewn prototypes to mainstream successes. The evolution of text-based games is traced through the lens of technological and sociocultural changes and the key role played by different programming languages.

Key concept: “On the peculiar terrain of literature-for-the-monitor, where the most innocent science fiction adventure may overlap with the most fashionable of nonreferential language theory, the future and the past are conducting their perennial transaction.”

2. 1971—THE OREGON TRAIL

This section discusses the creation of The Oregon Trail [1971], highlighting the importance of randomness and procedural rhetoric in the game. It analyzes how the game uses simple prose and limited technology to create an engaging and memorable experience. The game’s omission of certain historical realities, particularly the impact on Native Americans, is critiqued as an example of how games can perpetuate problematic narratives. This section also emphasizes the game’s lasting popularity and how it successfully engaged players through creating a simulated world and inviting them into it.

Key concept: “This program simulates a trip over the Oregon Trail from Independence, Missouri to Oregon City, Oregon in 1847. Your family of five will cover the 2000 mile Oregon Trail in 5-6 months — IF YOU MAKE IT ALIVE.”

3. 1972—ROCKET

This section examines the creation of the lunar landing game ROCKET [1972] and discusses its role in capturing the human experience of the space program through numerical simulation. While the game largely relies on numbers for its output, the strategic challenge and limited feedback create an immersive experience for players. This section also analyzes how the game was widely shared and adapted due to its publication in widely read resources and its simple code, highlighting how the early text-game community embraced sharing and iterating on each other’s work. Lastly, this section touches upon the genre of games inspired by ROCKET, emphasizing the lasting influence of this early experiment in simulation.

Key concept: “CONTROL CALLING LUNAR MODULE. MANUAL CONTROL IS NECESSARY”

4. 1973—HUNT THE WUMPUS

This section focuses on the creation of Hunt the Wumpus [1973], an early exploration game set in a dodecahedron-shaped cave system. The section highlights the game’s emphasis on strategic decision-making, unpredictable events, and spatial reasoning, which made it more compelling than many earlier computer games. Additionally, the game’s inclusion in an ongoing conversation about game design at the People’s Computer Company (PCC) contributed to its evolution and influence. The section concludes by emphasizing the role of shared spaces in shaping game design and how these spaces fostered a sense of community among early enthusiasts.

Key concept: “WELCOME TO ‘HUNT THE WUMPUS’ THE WUMPUS LIVES IN A CAVE OF 20 ROOMS. EACH ROOM HAS 3 TUNNELS LEADING TO OTHER ROOMS. (LOOK AT A DODECAHEDRON TO SEE HOW THIS WORKS-IF YOU DON’T KNOW WHAT A DODECAHEDRON IS, ASK SOMEONE)”

5. 1974—SUPER STAR TREK

This section explores the creation and legacy of Super Star Trek [1974], an early strategy game inspired by the Star Trek television series. It emphasizes how the game balanced playability with complexity, incorporating random generation and strategic elements that foreshadowed the roguelike genre. It also highlights the importance of community in the development and evolution of early text games, particularly through the exchange of program listings and modifications. The game’s influence on later space combat simulators and its cultural significance are also discussed.

Key concept: “YOUR ORDERS ARE AS FOLLOWS: DESTROY THE 10 KLINGON WARSHIPS WHICH HAVE INVADED THE GALAXY BEFORE THEY CAN ATTACK FEDERATION HEADQUARTERS ON STARDATE 2025; THIS GIVES YOU 25 DAYS. THERE ARE 4 STARBASES IN THE GALAXY FOR RESUPPLYING YOUR SHIP HIT ‘RETURN’ WHEN READY TO ASSUME COMMAND”

6. 1975—DND

This section discusses the creation of dnd [1975], an early text-based dungeon crawler inspired by the tabletop roleplaying game Dungeons & Dragons. It highlights the impact of the PLATO system’s advanced features (such as a touchscreen and custom fonts) on enabling more complex and immersive text games. The section also explores the emergence of a dedicated gamer subculture on PLATO, which often clashed with the educational goals of the platform, leading to tensions between gamers and administrators. Lastly, this section discusses the lineage of influence stemming from dnd to later dungeon crawlers and the eventual rise of graphical massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs).

Key concept: “What is thy name?”

7. 1976—ADVENTURE

This section examines the creation and impact of Adventure [1976], the first mainstream text adventure game. It highlights the game’s realistic descriptions of an underground cave system, inspired by the real-life caving experiences of its creator Will Crowther. This section emphasizes how Adventure’s simple, natural language parser and immersive world helped make it a blockbuster hit. It also discusses the game’s influence on the development of the genre, its role in jump-starting the computer game industry, and its enduring popularity as a template for countless later games.

Key concept: “YOU ARE STANDING AT THE END OF A ROAD BEFORE A SMALL BRICK BUILDING . AROUND YOU IS A FOREST. A SMALL STREAM FLOWS OUT OF THE BUILDING AND DOWN A GULLY.”

8. 1977—ZORK

This section explores the creation of Zork [1977], highlighting its evolution from a student project inspired by Adventure to a commercial success that would solidify the text adventure genre. It analyzes the role of the ARPANET in enabling early access and feedback from players, fostering a collaborative development process that led to a more polished and expansive game. This section emphasizes the significance of Zork’s parser, which supported multi-word commands and complex syntax, making it more sophisticated than its predecessors. It also discusses the game’s legacy, particularly its influence on the aesthetics of a generation of text games, and its role in shaping the future of interactive fiction through the development of the Z-machine and the Inform programming language.

Key concept: “You are in an open field west of a big white house, with a boarded front door. There is a small mailbox here.”

9. 1978—PIRATE ADVENTURE

This section tells the story of Pirate Adventure [1978], a text adventure created for early home computers with limited memory and processing power. This section examines how the game used a simplified engine and a unique “mission”-based goal to create a compelling experience, emphasizing the role of Alexis Adams in driving innovation at the company. It also highlights the challenges of fitting complex games into the small footprint of early microcomputers, and the technical limitations that could frustrate players. This section also discusses the unlikely success of Adventure International, the first company to focus exclusively on selling text adventures, and the important role of women in the early game industry, often overlooked by history.

Key concept: “I am in a Flat in london. Visible items: Flight of stairs. Sign says: “Bring TREASURES here, say: SCORE”. Bottle of rum. Rug. Safety sneakers. Sack of crackers. ——-> Tell me what to do? ”

10. 1979—CHOOSE YOUR OWN ADVENTURE

#1: THE CAVE OF TIME

This section explores the unlikely origins and cultural impact of the Choose Your Own Adventure [1979] series, a wildly successful experiment in interactive narrative that would capture the imagination of a generation of readers. It examines how the books gave readers a sense of agency over a story, allowing them to make decisions and shape the narrative in ways traditional prose did not. The section also analyzes how the series tapped into a larger cultural shift toward valuing choice and self-determination, which became increasingly prevalent in the 1980s. Lastly, this section discusses how the CYOA books, despite their simple format, inspired other experiments in interactive storytelling, both digital and analog, paving the way for a wider range of narratives and storytelling techniques.

Key concept: “WARNING ! ! ! ! Do not read this book straight through from beginning to end! These pages contain many different adventures you can go on in the Cave of Time. From time to time as you read along, you will be asked to make a choice. Your choice may lead to success or disaster!”

11. 1980—MUD

This section delves into the origin and development of MUD [1980], the first multi-user dungeon and progenitor of a genre that would evolve into massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs). It details how the game emerged from a student project, its innovative use of a shared memory space to enable multiplayer interaction, and the challenges of creating a compelling experience for multiple players. This section also explores how MUD’s mechanics and social dynamics evolved over time as its player base grew, shifting from a puzzle-focused dungeon crawler to a more open-ended world focused on freedom, player interaction, and the emergence of a unique online culture.

Key concept: “Narrow road between lands. You are stood on a narrow road between The Land and whence you came. To the north and south are the small foothills of a pair of majestic mountains, with a large wall running round. To the west the road continues…”

12. 1981—HIS MAJESTY’S SHIP “IMPETUOUS”

This section examines the creation of His Majesty’s Ship “Impetuous” [1981], a text adventure that experimented with a keyword-based approach to simulating natural language dialogue. It details the game’s unique format, which focused on key narrative moments rather than second-person commands, and how the system created an illusion of responsiveness through careful authoring and branching choices. It also highlights the game’s expansive prose, made possible by the larger storage capacity of floppy disks compared to earlier cassette-based systems, and how the game’s success helped pave the way for the commercialization of interactive fiction.

Key concept: “A WINDBLOWN STORY OF THE DAYS WHEN ONLY THE BRITISH FLEET OF FIGHTING SAIL KEPT THE FRENCH AND SPANISH NAVIES FROM SPREADING NAPOLEON’S TYRANNY ACROSS THE GLOBE.”

13. 1982—THE HOBBIT

This section explores the creation of The Hobbit [1982], an adaptation of the classic Tolkien novel that introduced dynamic NPCs with their own goals and motivations. The section highlights the game’s innovative use of procedural generation to create unique and unpredictable playthroughs, where even static objects could behave differently each time. It also emphasizes the technical challenges of implementing such a system in assembly code on a platform with limited resources, as well as the game’s lasting influence on the British home computing market and the development of the adventure game genre.

Key concept: “You are in a comfortable tunnel like hall To the east there is the round green door You see : the wooden chest. Gandalf. Gandalf is carrying a curious map. Thorin. Gandalf gives the curious map to you. Thorin sits down and starts singing about gold.”

14. 1983—SUSPENDED: A CRYOGENIC NIGHTMARE

This section explores the creation of Suspended [1983], a game that challenged many conventions of the text adventure genre by putting the player in control of a disembodied consciousness, tasked with directing a team of robots to save a dying world. The game’s unique interface, its complex system of interconnected challenges, and its focus on optimization and efficiency over plot and characterization made it stand out from its peers. The section highlights the critical and commercial success of Infocom, the company behind Suspended, and their ability to push the boundaries of interactive fiction while remaining commercially viable. It also examines the game’s legacy, particularly its impact on the perception of what a text adventure could be, and its influence on later games exploring similar themes of fractured realities and remote control.

Key concept: “FC ALERT! Planetside systems are deteriorating. FC imbalance detected. Emergency reviving systems completed. You are now in control of the complex.”

15. 1984—THE HITCHHIKER’S GUIDE TO THE GALAXY

This section explores the creation and enduring legacy of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy [1984], a game that successfully captured the humor and absurdity of Douglas Adams’s wildly popular franchise. The section examines how the game deconstructs traditional text adventure conventions, plays with the nature of interactivity, and uses an unreliable narrator to create a unique and memorable experience. It also highlights how the game’s popularity broadened the audience for interactive fiction, attracting many new players who were unfamiliar with the genre’s traditional tropes and puzzles.

Key concept: “You wake up. The room is spinning very gently round your head. Or at least it would be if you could see it which you can’t.”

16. 1985—A MIND FOREVER VOYAGING

This section delves into the creation of A Mind Forever Voyaging [1985], a text adventure that boldly tackled real-world political issues by simulating a plausible future shaped by conservative policies. The section examines how the game’s creator, Steve Meretzky, used interactive fiction’s ability to engage players deeply to explore the potential long-term consequences of Reaganomics, creating a cautionary tale for the present disguised as a game set in the future. It also explores the mixed reactions the game received, both from critics who struggled to analyze its unconventional approach and from players who were deeply moved by its prescient and thought-provoking themes.

Key concept: “You “hear” a message coming in on the official message line: “PRISM? Perelman here. The psych tests have all checked out at 100%, which means that you’ve recovered from the, ah, awakening without any trauma or other serious effects. We’ll be ready to begin the simulation soon…””

17. 1986—UNCLE ROGER

This section examines the creation of Uncle Roger [1986], a groundbreaking experiment in using a database as the foundation for an interactive narrative. The section explores how author Judy Malloy used the WELL BBS to tell her story in fragmented pieces, tagged with keywords and meant to be reassembled by readers, creating a “random-access narrative” that challenged traditional linear storytelling structures. It also highlights how the game captured the unique culture and social dynamics of the early Silicon Valley tech industry from a feminist perspective, exploring themes of gender roles and power dynamics rarely seen in computer games.

Key concept: “I drank too much red wine. The Broadthrow’s party is looping in my mind, nested with brief dreams and nightmares.”

18. 1987—PLUNDERED HEARTS

This section tells the story of Plundered Hearts [1987], Infocom’s first and only romance game, written by Amy Briggs, one of the first women to be hired as a full-time game designer at a major studio. It examines how the game navigates the conventions and stereotypes of historical romance, while also subverting some of them through strong female characters and a nuanced exploration of gender roles. It also highlights the challenges Briggs faced in bringing her vision to life, particularly the lack of understanding and appreciation for romance within the mostly male gaming community at the time.

Key concept: “>SHOOT THE PIRATE Trembling, you fire the heavy arquebus. You hear its loud report over the roaring wind, yet the dark figure still approaches. The gun falls from your nerveless hands. “You won’t kill me,” he says, stepping over the weapon. “Not when I am the only protection you have from Jean Lafond.” Chestnut hair, tousled by the wind, frames the tanned oval of his face. Lips curving, his eyes rake over your inadequately dressed body, the damp chemise clinging to your legs and heaving bosom, your gleaming hair. You are intensely aware of the strength of his hard seaworn body, of the deep sea blue of his eyes. And then his mouth is on yours, lips parted, demanding, and you arch into his kiss… He presses you against him, head bent. “But who, my dear,” he whispers into your hair, “will protect you from me?””

19. 1988—P.R.E.S.T.A.V.B.A. (P.E.R.E.S.T.R.O.I.K.A.)

This section tells the story of P.R.E.S.T.A.V.B.A. [1988], a subversive text adventure created in Czechoslovakia under a totalitarian regime. The section explores the challenges of accessing and creating games in a country where personal computers were rare and censorship was widespread. It examines how the game used humor and satire to critique the regime’s outdated Soviet ideals, and how its release coincided with a period of political upheaval and growing dissent that would eventually lead to the Velvet Revolution. Lastly, it highlights the importance of games as a means of self-expression and social commentary, particularly in contexts where other forms of expression are suppressed.

Key concept: “CENTRAL COMMITTEE SOFTWARE ON THE OCCASION OF THE 20TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE LIBERATION OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA BY WARSAW PACT ARMIES WOULD LIKE TO OFFER A CONVERSATIONAL PUZZLE GAME: P.E.R.E.S.T.R.O.I.K.A.”

20. 1989—MONSTER ISLAND

This section delves into the world of play-by-mail (PBM) games with a focus on Monster Island [1989], a groundbreaking title that pushed the boundaries of the genre with its ambitious scope and complex simulation. The section explores the unique challenges of creating and running a PBM game, particularly the difficulties of coordinating gameplay and communication between players in a pre-internet world. It also examines how the game’s design fostered a strong sense of community and collaboration among players, who relied on fanzines and in-game groups to share information and solve the game’s many mysteries. Lastly, it discusses the impact of the internet on the PBM genre, both its role in accelerating its demise and in enabling new forms of play-by-email games to flourish.

Key concept: “MONSTER ISLAND is a whole new type of Play-by-mail game. It is a strange game, unlike anything you’ve seen. Throw away any preconceived ideas you may have; MONSTER ISLAND has its own special feel and works in a very intelligent way.”

21. 1990—LAMBDAMOO

This section explores the rise of LambdaMOO [1990] and the evolution of text-based virtual worlds from niche hobbyist spaces to vibrant online communities with thousands of players. It traces the lineage of influence from early MUDs to the emergence of object-oriented programming, which enabled a new level of player creativity and collaborative worldbuilding. This section highlights the MOO’s unique culture and its impact on early internet discourse, particularly around issues of identity, social dynamics, and the challenges of governing online spaces. It also examines the MOO’s legacy, particularly its role in shaping the development of later online communities and its enduring appeal to a dedicated group of enthusiasts.

Key concept: “LambdaMOO is a new kind of society, where thousands of people voluntarily come together from all over the world. What these people say or do may not always be to your liking; as when visiting any international city, it is wise to be careful who you associate with and what you say.”

22. 1991—TRADE WARS 2002

This section delves into the world of BBS door games with a focus on Trade Wars 2002 [1991], the most popular BBS game of all time. It explores the evolution of the game from earlier space trading and combat simulators, its deep and rewarding gameplay, and the strategies employed by its creators to foster a sense of community and competition among players. The section also highlights the importance of ANSI graphics in making text-based games more visually appealing and engaging, and the challenges of adapting to a rapidly changing online landscape as dial-up gave way to broadband and internet service providers began to offer their own multiplayer gaming experiences.

Key concept: “What is your name? ZAPHOD Use ANSI graphics? Y”

23. 1992—SILVERWOLF

This section explores the story of Silverwolf [1992], a text adventure created by the enigmatic St. Bride’s School, an organization that blurred the lines between reality and fantasy through its unique blend of education, roleplaying, and game development. The section examines the creation and themes of Silverwolf, a game based on a feminist fantasy serial, and its reception by a gaming community struggling to understand the school’s often contradictory and mysterious identity. It also delves into the challenges of categorizing and understanding the St. Bride’s games within the context of a still-evolving medium, and the difficult legacy of a group whose progressive ideas around representation were often intertwined with troubling hints of social conservatism and exclusion.

Key concept: “Not so much a programme more a way of life,”

24. 1993—CURSES

This section traces the development of Inform, a programming language created by Graham Nelson to enable the creation of new games that ran in Infocom’s Z-machine. The section highlights the collaborative efforts of reverse-engineering Infocom’s game format and the influence of the Lost Treasures of Infocom collection on inspiring a new generation of interactive fiction creators. It explores how Nelson’s work led to a resurgence of interest in text games and helped establish a new standard for interactive fiction through its simplified syntax, robust library of standard behaviors, and focus on creating immersive simulated worlds. It also examines the development of Curses [1993], the first game written in Inform, and its role in showcasing the language’s capabilities and solidifying a new direction for interactive fiction.

Key concept: “Infocom game story files are as near to a universal format as we have for interactive fiction games, but until now it has been very difficult to construct them, and I am not aware that anyone has previously created them outside of Infocom itself.”

25. 1994—THE PLAYGROUND

This section examines the Oz Project’s groundbreaking research into interactive storytelling and believable AI agents, focusing on Scott Neal Reilly’s work on developing a system for characters with emotions that could influence their behavior in a game world. The section explores how Reilly’s approach differed from traditional AI techniques, drawing inspiration from storytelling and animation rather than logic and optimization, to create characters whose behaviors were less about finding optimal solutions and more about expressing their personality and reacting realistically to changing circumstances. The section also discusses the inherent challenges of this approach, particularly the difficulty of debugging complex emergent behavior, and the long-term influence of the Oz project on inspiring new generations of interactive storytellers.

Key concept: “Traditional AI goals of creating competence and building models of human cognition are only tangentially related because creating believability is not the same as creating intelligence or realism. Therefore, the tools that have been designed for those tasks are not appropriate.”

26. 1995—PATCHWORK GIRL; OR, A MODERN MONSTER

This section explores the creation of Patchwork Girl [1995], a groundbreaking hypertext novel that challenged traditional notions of narrative structure and identity through a fragmented and interwoven story. This section explores how author Shelley Jackson used the visual capabilities of Storyspace to construct a layered and multi-faceted experience for readers, encouraging them to actively engage with the text by piecing together fragments, exploring alternate paths, and constructing their own understanding of the story. It also delves into the themes of the novel, including the nature of identity, gender, and the body, and how Jackson’s use of collage and appropriation reflected those themes both in the story itself and in the way it was presented.

Key concept: “I am buried here. You can resurrect me, but only piecemeal. If you want to see the whole, you will have to sew me together yourself.”

27. 1996—SO FAR

This section examines the creation of So Far [1996], an ambitious parser game that pushed the boundaries of interactive fiction with its complex system of interconnected puzzles, surreal environments, and a story that explored themes of memory, loss, and the search for meaning. The section explores how the game’s unconventional design and challenging puzzles led to mixed reactions from players, some of whom found it frustratingly difficult while others were captivated by its unique approach and thought-provoking themes. It also discusses the game’s influence on the evolution of interactive fiction, particularly its role in encouraging a greater focus on storytelling and experimentation with new forms of narrative.

Key concept: “Hot, foul, and dark. How did indoor theater become so fashionable? Well enough in spring rain or winter, but not in the thick, dead afternoon of high summer. And though Rito and Imita looks very fine, shining with electric moonslight in the enclosed gloom, you’re much more aware of being crammed in neck-by-neck with your sweaty fellow citizens.”

28. 1997—ACHAEA: DREAM OF DIVINE LANDS

This section examines Achaea [1997], a text-based MUD that thrived in an era increasingly dominated by graphical MMORPGs. It explores how the game’s creator, Matt Mihály, focused on building a rich, roleplay-driven world with complex systems for politics, religion, and combat to differentiate it from its graphically sophisticated competitors. The section highlights how Achaea used microtransactions, a model then uncommon in the industry, to fund its development and operations, becoming one of the first commercially successful “free-to-play” games. It also explores the game’s evolving design and mechanics, its dedicated player base, and its role in demonstrating that text games could still offer compelling and immersive experiences even in the face of increasing competition from graphically advanced titles.

Key concept: “Your fate and fame shall be an echo and a light unto eternity.”

29. 2018—WEYRWOOD

This section tells the story of Weyrwood [2018], a choice-based interactive fiction romance set in a world of magic and societal intrigue. The section explores the game’s creation by first-time game developer Isabella Shaw, a classically trained singer and writer who was drawn to the possibilities of interactive storytelling through the user-friendly development tools and platform provided by Choice of Games. It examines how Weyrwood’s design exemplifies the company’s focus on creating games driven by meaningful choices, exploring complex themes of social dynamics, romance, and morality through a system of branching paths and accumulating stats. It also discusses the growing popularity of choice-based interactive fiction in the 2010s, its impact on the commercial viability of the genre, and the changing role of women and other underrepresented voices in shaping the stories games tell.

Key concept: “The heavy door to Messrs Holwood, Holwood, and Pende’s law firm closes firmly behind you, leaving you in the street.

30. 2019—AI DUNGEON

This section delves into the creation and impact of AI Dungeon [2019], a text adventure that uses an AI text generator to dynamically create content in response to player input. It explores how the game’s creator, Nick Walton, harnessed the power of OpenAI’s GPT-2 language model to create an open-ended and unpredictable experience, pushing the boundaries of interactive storytelling and blurring the line between human and machine creativity. The section highlights the challenges and controversies surrounding the use of AI in game development, including the potential for misuse, the ethical implications of using scraped training data, and the difficulty of defining authorship and ownership in a collaborative human-machine context. It also examines how the game’s viral success forced its creators to confront issues of scalability, cost, and content moderation, while also inspiring a new wave of interest in the possibilities and perils of AI-driven storytelling.

Key concept: “Generally, a game—even a procedurally generated game—begins with an idea of what you can do and how exactly it expects things to play out. AI Dungeon is not one of those games.”

31. 2020—SCENTS & SEMIOSIS

This section explores the creation of Scents & Semiosis [2020], a procedural text game that uses an elaborately handcrafted system of rules and generators to create an endless variety of scents, bottles, and associated memories. The section examines how the game’s creator, Sam Kabo Ashwell, drew inspiration from both perfumery and Emily Short’s five principles of procedural content generation to design a system that could produce surprising, evocative, and internally consistent outputs despite its randomness. It also discusses how Ashwell collaborated with other interactive fiction authors to expand the game’s scope and thematic possibilities, and how the game’s unique blend of personal storytelling and procedural generation reflects the evolving landscape of interactive fiction in the 2010s, a decade where new tools and communities opened up the form to a wider range of creators and audiences.

Key concept: “There are other perfume-boxes, other lists, sharply curated according to audience. You allow yourself a degree of sentiment in their selection, but that too serves a public purpose. This collection—messy, unfashionable, incoherently themed—is an entirely private matter. A giant’s secret heart.

Essential Questions

1. Why are text games important, and why should we care about their history?

This book explores how text games, despite often being overlooked and dismissed, have played a vital role in shaping the history of computer games and interactive storytelling. It highlights their ability to pioneer new genres and mechanics, explore innovative ways of telling stories, and showcase the creative potential of language as a medium for play. The book argues that text games are worthy of remembrance and study due to their unique contributions to gaming history and their enduring influence on contemporary game design.

2. What is a text game, and how has its definition evolved over time?

Text games have always existed in a liminal space between literature and games, often struggling to be taken seriously by both communities. The book explores this tension through examining the aspirations of early creators, the evolving discourse around interactive fiction, and the challenges faced by text game developers in finding an audience and achieving mainstream success. It highlights how technological limitations, changing cultural values, and the rise of graphically-rich games have shaped the genre’s evolution, pushing it to continually adapt and redefine itself.

3. What role have communities played in shaping the history and design of text games?

The book argues that communities have been essential to the development and evolution of text games. Early games were often shared and modified in person, but the rise of the internet—from the ARPANET to the modern web—created online spaces for collaboration, conversation, and information sharing that accelerated the genre’s progress. The book highlights the role of online communities like the People’s Computer Company, the rec.arts.int-fiction newsgroup, and the Cloudmakers in shaping game design, fostering innovation, and providing a platform for new voices and perspectives.

4. How have text game creators experimented with the form, and what lessons can we learn from their experiments?

This book explores how text game creators have consistently pushed the boundaries of what a computer game can do, experimenting with new forms of storytelling, innovative interfaces, and unexpected gameplay experiences. From the early days of simple simulations like “The Oregon Trail” to the complex narratives of “Photopia” and the dynamic character interactions of “Achaea,” text game authors have consistently sought to find new ways to engage players with their worlds and stories. The book argues that text games have often served as a space for experimentation and innovation, paving the way for new genres and mechanics that would later find success in graphically-rich games.

5. How can a game without graphics be compelling, and what unique advantages might text offer for interactive storytelling?

The book examines how text games, despite their lack of visuals, can offer profoundly immersive and engaging experiences through evocative language, compelling narratives, and engaging mechanics. It argues that the right words can create vivid pictures in the reader’s mind, and that interactive fiction in particular has the unique ability to make players feel like they are part of the story being told. The book suggests that text games can transport players to worlds of unlimited resolution and perfect fidelity, and that their lack of visuals can be a strength, forcing players to more actively engage their imagination and participate in the process of worldbuilding.

Key Takeaways

1. Games are powerful storytelling mediums, even without graphics.

The book demonstrates that stories are not merely a decorative element of games, but a foundational part of what makes them compelling and memorable. Text games, despite their lack of visuals, often excel at storytelling by relying on evocative language, interesting characters, and the player’s imagination to fill in the blanks.

Practical Application:

In the field of AI, understanding the power of storytelling can help engineers design systems that are not only functional but also engaging and relatable. For example, a chatbot might be designed to tell stories about its creation or its purpose, helping users connect with it on a more human level.

2. Limitations can drive creativity and lead to innovation in game design.

The book explores how many of the most innovative text games were born from limitations in technology, forcing creators to find creative solutions and explore new possibilities within a constrained space.

Practical Application:

In product design, understanding how limitations can drive creativity can help designers find innovative solutions and create truly unique experiences. For instance, limitations in processing power or memory might lead to a minimalist design aesthetic or a focus on innovative mechanics rather than complex graphics.

3. Communities are vital to the success and longevity of interactive experiences.

From the earliest days of text adventures, players have been modifying, extending, and sharing games with each other. The book highlights how the rise of online communities, from the ARPANET to the modern web, dramatically accelerated this process, fostering a collaborative spirit and a sense of shared ownership over the games being created and played.

Practical Application:

In community management, understanding how to foster a sense of ownership and agency among users can help build stronger and more sustainable communities. This might involve providing tools for users to contribute content, shape community guidelines, or moderate discussions themselves.

4. Playfulness and humor are powerful tools for engaging players.

Many of the most fondly remembered text games have leaned into humor and playful language as a way to create a more engaging and memorable experience. The book demonstrates that even simple mechanics like making numbers go up can be more compelling when wrapped in a veneer of playful language and absurdity.

Practical Application:

AI systems can be designed to be more playful and engaging by incorporating elements of humor, surprise, and even randomness. A chatbot, for instance, might be programmed to tell jokes or offer unexpected responses to certain prompts, making interactions with it feel more human and less predictable.

Suggested Deep Dive

Chapter: 1985—A Mind Forever Voyaging

This chapter explores how games can be used to explore complex social and political issues. It’s particularly relevant to AI product engineers as it highlights the potential for AI-powered games to engage with real-world problems and promote critical thinking.

Memorable Quotes

Introduction. 27

“On the peculiar terrain of literature-for-the-monitor, where the most innocent science fiction adventure may overlap with the most fashionable of nonreferential language theory, the future and the past are conducting their perennial transaction.”

1971—THE OREGON TRAIL. 66

Though the game does nothing with the answers, the mere fact of being asked makes you feel like a part of the story being told. It was a trick that would continue to work across half a century of computer games and counting; a good reminder that no game is too old to learn from.

1973—HUNT THE WUMPUS. 84

IMAGINE YOURSELF AN EXPLORER, Dave Kaufman’s Caves began—and in the years to come, more and more computer users would do just that.

1977—ZORK. 129

“We were learning how to write adventure games,” Lebling wistfully recalls, “and it took a long time to learn to do them better.”

1985—A MIND FOREVER VOYAGING. 245

“So many of the things I was worried about in the 1980s have come to pass,” Meretzky noted in 2017. “All of the warmongering and trickle-down economics produced exactly the sort of results I was afraid of.”

Comparative Analysis

“50 Years of Text Games” distinguishes itself from other histories of digital games by its dedicated focus on text-based games. Unlike broader surveys that often prioritize graphically-rich titles, this book delves into the unique lineage and evolution of interactive fiction, MUDs, and other text-driven experiences. It complements works like “Twisty Little Passages” by Nick Montfort, which provides a more in-depth analysis of a particular subgenre, by offering a broader historical overview and connecting individual games to larger trends in technology and culture. While many other game histories focus primarily on commercial successes, this book also celebrates the work of amateur and independent creators, recognizing their often overlooked contributions to the field. It echoes arguments made by scholars like Espen Aarseth about the importance of considering games as meaningful cultural artifacts, and by Brenda Laurel about the potential for dynamic and interactive storytelling in digital mediums.

Reflection

50 Years of Text Games explores a rich and often overlooked history, highlighting the creativity and ingenuity of game designers working within the constraints of text-based mediums. While the book celebrates the technical and narrative innovations of these games, it also acknowledges the inherent biases and limitations embedded within them. It reminds us that even seemingly simple games can encode opinions and perpetuate problematic narratives, and that the seemingly neutral logic of an algorithm can mask harmful ideologies. By placing these games within a larger social and historical context, the book invites us to reflect not only on how far interactive storytelling has come, but on where it might—and should—go next. The book’s focus on the past also provides a compelling lens through which to understand the present. The resurgence of interactive fiction, the rise of text-based mobile games, and the renewed interest in conversational AI all point to an ongoing fascination with the possibilities of language as a medium for play. And while the book’s account ends in 2020, the story of text games is far from over. As new technologies emerge and new generations of creators take up the mantle, the games of the future will likely continue to draw inspiration from the innovations and experiments of the past, building on the legacy of those who first dared to dream of worlds made of words.

Flashcards

What is BASIC?

A programming language invented at Dartmouth in 1964, known for its simplicity and ease of use. It enabled a wider range of people to learn to code and create their own programs, including games.

What is Adventure?

A text adventure game released in 1976, considered the first mainstream hit of the genre and often credited with popularizing interactive fiction.

What is MUD?

A pioneering text-based multi-user dungeon (MUD) created in 1980 by Roy Trubshaw and Richard Bartle.

What is Zork?

A text adventure game released in 1981 by Infocom, known for its large, complex world, sophisticated parser, and innovative use of in-game feelies.

What is The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy?

A text adventure game released in 1984 by Infocom, notable for its faithful adaptation of Douglas Adams’s humor and the way it deconstructs traditional text adventure conventions.

What is Ren’Py?

A visual novel engine created by Tom Rothamel and released in 2004, known for its user-friendly interface and cross-platform compatibility. It revolutionized visual novel development and enabled a new generation of creators.

What is Curses?

A text adventure game released in 1993 by Graham Nelson, notable for being the first game written in the Inform programming language and for demonstrating the possibilities of creating complex and immersive text-based games.

What is Twine?

A hypertext authoring tool created by Chris Klimas and released in 2009. Its ease of use and visual interface opened up interactive storytelling to a wider range of creators, leading to an explosion of new and experimental games.